Kicker Managerspiel as a Knapsack Problem

The Problem

Every year the German football magazine kicker hosts a virtual manager game. Before the start of the Bundesliga season, you can select your team from all Bundesliga squads for a with a given budget. For the 1. Bundesliga the budget is 42.5 million euros, for lower leagues accordingly lesser. The prices of the players a determined by kicker and are based on past performances and the ability of a player. A world class striker like Robert Lewandowski costs 8.5 million € (a huge portion of your budget), but he has proven to be a goal scoring machine which constantly delivers. On the other side, an unknown youth player costs only 0.2 million € but might never even play. The goal of the game is, to select a team that yields a maximum of points during the season (34 matchdays). The points are based on how your players performed in the actual games. For example, you get points if a player scores a goal, your goalie keeps a clean sheet or in general gets a good rating. But if your player performs badly or gets a red card you can also get negative points. Besides the team budget the team selection has the following additional restrictions:

- 22 players

- 3 goalies, 6 defenders, 8 midfielders, 5 strikers

- a maximum of 4 players of one team

- a maximum of 3 players of one team in your starting 11

Before each matchday you can select 11 out of your 22 players with one of the following tactical formations (1 goaly plus x defenders, y midfielders, z strikers):

- 3-5-2

- 4-5-1

- 4-4-2

- 4-3-3

- 3-4-3

Only the players you selected will get points. So based on the matchday, injuries, and current form you can adjust your team. However, you can’t change your select 22 players for the half season (17 games). Only during the winter break, you can transfer 4 players (I detail this procedure later in detail as an additional problem). So overall the main problem is to select a team which gets a maximum number of points under a given set of constraints. An experienced user could either pick a team which consists of a very strong starting 11 and only cheap substitutes or select a team of 22 middle priced players. While the latter gives you more options to react to injuries and form variations, only the primer all-or-nothing approach gives you chances for a good position in the leaderboard.

The Solution

The problem of a players selection under given restrictions can be modeled as a constrained knapsack problem. This can be nicely modeled with the open-source Java-based framework Opt4J utilizing Evolutionary Algorithms (EA) and Boolean Satisfiability (SAT). According to Lukasiewycz et al., this approach has three different parts:

- in the chromosome space you create a genotype

- in the decision space you decode your genotype to a phenotype

- and you evaluate your phenotype in the in the objective space

According to the evaluation, you keep Pareto-optimal solutions in your archive and can perform crossover and mutation on the individuals of your population. The nice thing about combining EAs and SAT is that infeasible solutions, i.e. constraint violations, are found by the SAT solver and your search space can be efficiently be pruned.

Creator/Decoder

Enough of theory, let’s start implementing.

First, we need all the players from where we want to select our team.

For each league, there exists a different problem class.

For example, for the 1. Bundesliga we instantiate a FirstLeagueManagerSpielProblem object.

In this class, we read the players from a csv file copied from the kicker web side.

The function getPlayers() returns a collection of all the players of the league.

Collection<Player> playerList = problem.getPlayers();

A player is characterized by a unique name, his club, his tactical position, is price (value), and the points (the average rating is not used for the optimization, as the leaderboard only relies on points):

public class Player implements Comparable<Player> {

private String name;

private String club;

private String position;

private float value;

private int points;

private float rating;

...

}

The set of constraints for the player selection is specified in ManagerSpielSATCreatorDecoder:

Set<Constraint> constraints = new HashSet<Constraint>();

First, the constraint of 22 players and the 4 different tactical positions (tor=goaly, abw=defenders, mit=midfield, stu=strikers):

torConstraint = new Constraint(Operator.EQ, 3);

abwConstraint = new Constraint(Operator.EQ, 6);

mitConstraint = new Constraint(Operator.EQ, 8);

stuConstraint = new Constraint(Operator.EQ, 5);

The constraints are specified in a Pseudo Boolean fashion.

In the ‘Constraint’ constructor the right-hand side is specified.

For example, there should be exactly (EQ: equal) 3 goalkeepers.

In addition, less equal (LE) and greater equal (GE) are supported.

For the left-hand side, a player is set to true (1) if selected or to false (0) otherwise.

The coefficient (first argument of the add function) is 1 in our case.

switch (player.getPosition()) {

case Positions.TOR:

torConstraint.add(1, new Literal(player, true));

break;

case Positions.ABW:

abwConstraint.add(1, new Literal(player, true));

break;

case Positions.MIT:

mitConstraint.add(1, new Literal(player, true));

break;

case Positions.STU:

stuConstraint.add(1, new Literal(player, true));

break;

default:

System.err.println("Undefined Position");

}

As Pseudo-Boolean constraints only accept an integer as constants the budget constraints need to convert from millions to hundred thousands of euros:

maxValueConstraint.add((int) (player.getValue() * 100), new Literal(player, true));

But it turns out that this constraint keeps the SAT solver very busy and slows down the optimization process massively. This is why I shifted this constraint to the evaluator where it is checked without SAT.

Finally, the constraint that only 4 players of one team can be in the selection is coded as follows:

if (!maxPlayerPerTeamConstraints.containsKey(player.getClub())) {

Constraint clubConstraint = new Constraint(Operator.LE, 4);

maxPlayerPerTeamConstraints.put(player.getClub(),clubConstraint);

}

maxPlayerPerTeamConstraints.get(player.getClub()).add(1, new Literal(player, true));

The player collection and the constraints are handed over to the SAT solver, which checks if the selection of the players is feasible, i.e. doesn’t violate any constraints. We get the selected players here:

public PlayerSelection convertModel(Model model) {

PlayerSelection playerSelection = new PlayerSelection();

for (Player player : problem.getPlayers()) {

if (model.get(player)) {

playerSelection.add(player);

}

}

return playerSelection;

}

Winter Transfers

After 17 matchdays there is the possibility to transfer any 4 players of our team (while ensuring the budget constraint). I modeled this with an additional constraint, that at least 18 players need to be selected from the initial team:

winterConstraint= new Constraint(Operator.GE, 18);

...

for (Player player : playerList) {

for (Player player2 : winterplayers) {

if (player2.getName().equals(player.getName()))

winterConstraint.add(1, new Literal(player, true));

}

...

}

This slows down the optimization quite a bit but does only need slight modifications to the code and keep the base problem encoding unchanged. An encoding, which starts from the given playerlist of 22 and exchanges 4 players out of it may be more performant but is a different problem.

Evaluator

The goal of the evaluator is to quantify the found solution. The quantification can be done regarding multiple objectives. In the given case, not only the overall number of points should be maximized, but also the number of points of a given tactical formation. To ensure that we only have 3 players of one team in our starting 11, we first get the 11 best players of our team selection. The we check that there maximal 3 players of the same club in it:

Collections.sort(playerList,(p1, p2) -> p2.getPoints1516() - p1.getPoints1516());

List<Player> starting11 = playerList.subList(0, 11);

starting11.forEach(player -> increaseClubCount(clubCountStarting11, player));

// max 3 players of same team in starting 11

playerSelection.setFeasible(Collections.max(clubCountStarting11.values()) <= 3);

Afterwards, we calculate the points of each formation and check if the budget constraint is met. If the team budget is exceeded, we set the solution to infeasible:

playerSelection.setFeasible(false);

Optimization

With some additional helper and I/O classes, we are ready to go and let the optimizer do the work. We can specify the population size (how many different solutions we want to check in each generation), the archive size (number of Pareto-optimal solutions we save), crossover rate etc… After some generations, our solutions will converge and no new Pareto optimal solutions can be found anymore. However, as the optimization is a metaheuristic and initial solutions, crossover, and mutations are non-deterministic, each run may result in slightly different solutions.

Results

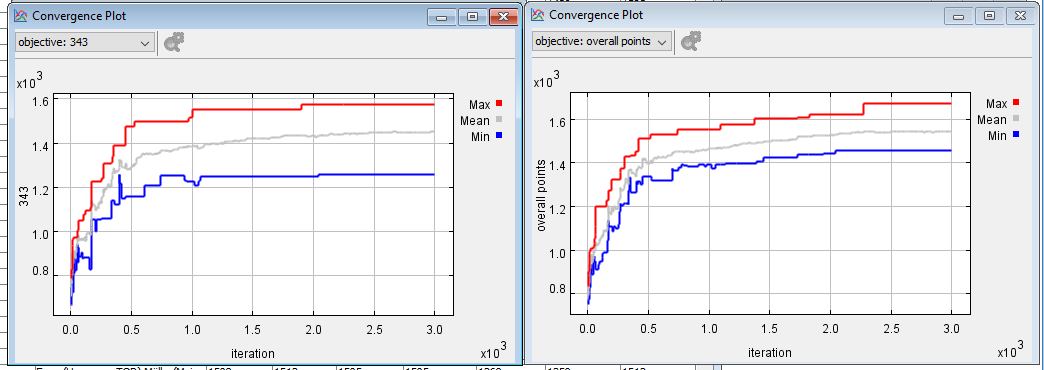

Opt4J provides a modular framework with nice visualization possibilities. After klicking together the “kicker problem” with our creator/decoder, evaluator, a logger etc., we can watch our optimization converge over time. In the following screenshot you can see improvements until 2500 iterations for two tactical formations we optimze for.

Our optimization finishes after the specified 3000 iterations which takes roughly one minute.

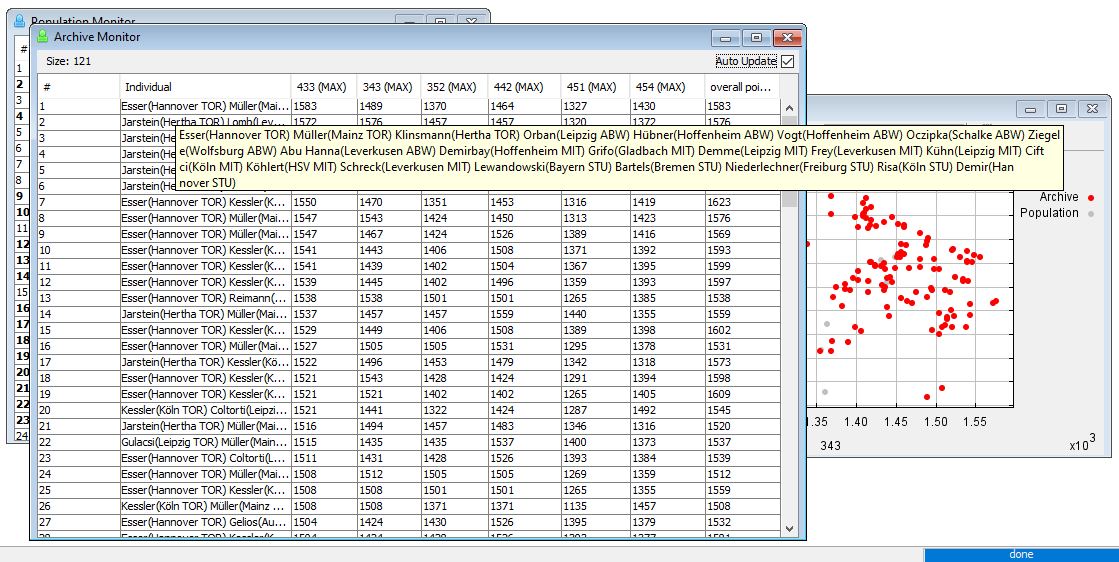

We have 121 Pareto-optimal solutions in our archive.

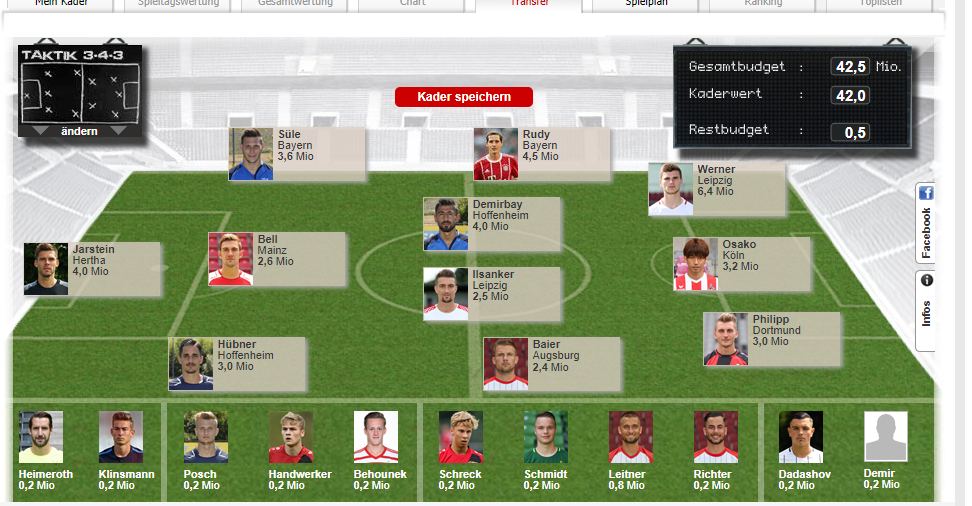

For example, we found a 4-3-3 squad with 1583 points and and overall points of also 1583 points.

This means that all the points stem from the starting eleven und the bench players contribute nothing.

We also see that there is a solution with a team with 1602 points where the best 4-3-3 selection only has 1529 points.

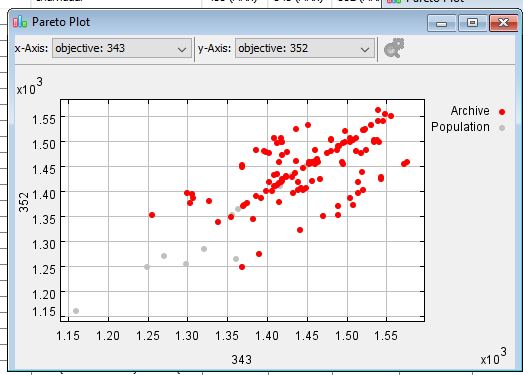

If we take a closer look to the Pareto-front (or the 2D representation of 2 objectives), we can see that 3-4-3 and 3-5-2 formations are correlated.

If we take a closer look to the Pareto-front (or the 2D representation of 2 objectives), we can see that 3-4-3 and 3-5-2 formations are correlated.

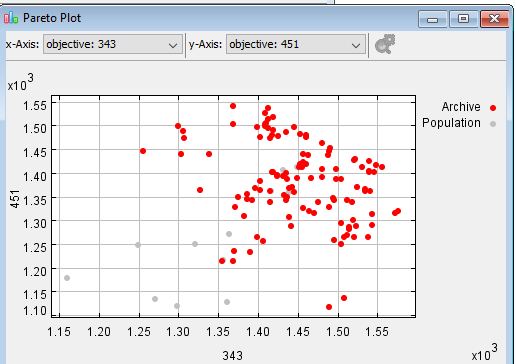

In contrary, an optimized 3-4-3 formation and an optimized 4-5-1 formation look quite different. Which is quite obvious as you need 3 good strikers in the one formation and only 1 in the other.

Finally, an optimized squad, which I didn’t use:

Limitations and Outlook

Perfect, now we have a machine optimized team which utilizes nicely our budget and maximizes the points. A human couldn’t do it like this. So problem solved? Not really. Currently, the points, the base of the optimization, are solely based on the last season. If the players who get the same points in the current season, the team would be optimal. However, in reality, the points will change. A young prospect who never played Bundesliga will have a breakthrough and make a lot of points for a few euros. For example, Dennis Geiger from Hoffenheim made a lot of points while his price is only 0.2 million €. Based on the pre-season, at least some points could be expected and the player was in the selection of a lot of human experts. For the optimized, it was only any of the players with 0 points. On contrary, a player who made a lot of points last season now plays for a bigger club and gains less play time aka points. This holds true for players like Sebastian Rudy. If still playing for Hoffenheim, he would be a bargain, as a Bayern player he is not. Using points from past seasons, we can also come up with some time series predictions using machine learning (e.g. regression, RNNs). Unfortunately, kicker only provides the points from the last season. I started with a preliminary, prediction based on two seasons here. However, the results are not really satisfying and don’t address completely the aforementioned problems. An idea here would be, to combine this data with data from whoscored.com or some other website with player statistics for a better predictions model. With this data, maybe a trend in the player’s development could be predicted (promising prospect or declining player). Overall, the optimization can currently give some hints and guide the team selection but cannot compete with a handpicked solution based on experience, pre-season impressions, and luck.